By Dorothea Depner

One week ago, on the morning of the launch of our new exhibition in the State Apartments, Making Majesty, I met up with the two curators Myles Campbell and William Derham to find out a bit more about the project they had been working on for almost two years.

DD: Where did the idea for this exhibition come from and what story did you want to tell with Making Majesty?

WD: The idea began as a discussion following our previous project, a small exhibition to mark 200 years of the Chapel Royal at Dublin Castle. We came across such a wealth of information that had been previously untapped, especially the Board of Works papers in the National Archives. So we started probing parts of all this untapped information and discussing what we should focus on.

MC: I think it’s the human story for me that is the interesting one: what motivates someone to create a very showy space – and in some cases pay for it out of their own pocket – when they’re only here as viceroy for a few years? We know so much about Dublin Castle as a bastion of British rule for hundreds of years, and I think that narrative can be a reductive one with little nuance and depth to it. The story I wanted to tell was of the individual motivations behind the development of these rooms and grand spaces in the State Apartments. Was it to create a grand image of the British institutions here? Was it to create an image of individual viceroys and their own aspirations? Were they trying to further their own aims? Was it to create an impressive image of the king and the court in London? We had very few answers to all these questions. We knew that a lot of personal time and effort was invested by the viceroys and the people around them to create all this, but we didn’t really know why, and we didn’t know exactly what the extent of that work was either. So it was, I suppose, to try and understand that story behind the creation of these very grand spaces and to try and retrieve some of the motivation behind that.

William Turner De Lond, George IV, King of England, entering Dublin, 1821

DD: I am curious to find out how you decided which objects were best suited to tell your story?

MC: We thought about it carefully and it occurred to us that there were various ways in which this image was created and through various media: through architecture, obviously – the Castle is a building – but also the social history that unfolded within and around it, the ceremonial. And then also through the furnishings that were ordered and procured for it. So those three things stood out to us. We also tried to include other elements like costume, music and food, and it worked quite well to dedicate each of the exhibition rooms to different themes such as architecture, performance, craftsmanship, and then try to capture broadly through the right objects the pantheon of different activities they were engaging in to create this image. Some objects were very obvious, for example, the Sword of State is obviously very appropriate to tell the story of ceremony. It’s the only object of its kind that you could use. Whereas a royal portrait can tell you about how a monarch is represented, but you can use almost any royal portrait, I suppose, to illustrate that part of the story. But there is only one sword.

DD: A lot of the objects in the exhibition are on loan from other institutions in Ireland and abroad. What was your biggest scoop?

MC: Inevitably, you have to say it was the Irish Sword of State. It came from the Jewel House in the Tower of London. It is normally on display just around the corner from where the crown jewels are. Historically, it is extremely valuable and significant. It was quite a scoop! The sword was commissioned in 1660 by King Charles II after he was restored and had vanquished Cromwell. It symbolised the power and authority of the monarch in Ireland. It came here in about 1661 and remained in the Castle until 1922. For considerable amounts of that time it rested across the throne that is still there in the Throne Room today. It was also carried as part of all these great ceremonial processions in front of the procession to indicate the monarch’s power in the absence of the monarch. As a central part of the ceremonial we felt it would be an interesting thing to bring here and I suppose a way of understanding the power of that regime and also the kind of regime against which independent Ireland has defined itself. It’s a good way of understanding where we have come from as a nation. No object, more than that sword, gives us such a tangible insight into how royal authority was represented in Ireland in the past.

WD: It was also a useful temporal touchstone, if you like, because it was the one thing that throughout all the change at Dublin Castle – the different throne rooms, the different decoration schemes – was the one thing that was a constant and around which each room would have been organised or decorated.

At the launch: William Derham, Mary Heffernan (General Manager Dublin Castle), Maurice Buckley (Chairman OPW) and Myles Campbell assembled around the Irish Sword of State

DD: You’ve spent almost two years researching, preparing and then installing this exhibition. Have you become attached to a particular exhibit in the process?

MC: My favourite object is probably a small print depicting Queen Victoria during her final visit to Dublin in 1900. It shows her passing a laneway in her carriage. She is looking directly ahead and so she seems unaware of the poverty of the people who live there. Some of the people are barefoot and their washing hangs from makeshift clothes lines. The small scale of their homes and the evident poverty in which they live makes for such a striking contrast to the image of a prosperous, loyal city that we see in other prints in the exhibition. During the research for the show, we came across countless prints depicting the crowded, stately streets of Dublin, where wealthy spectators had turned out to wave their hats and cheer the royal visitors. But this particular print was the only one we came across from a royal visit that really reflected the widespread poverty beyond those streets and across many parts of Ireland. I think the fact that the poverty of many Dublin streets often failed to make an impact on royal visitors tells us something about the success of the Dublin Castle and city authorities in helping to create a deceptively positive image of the city during these visits. This kind of depiction doesn’t fit easily with the image of a benevolent administration presiding over a contented people. For this reason, I think it tells us a different and important story about the Castle’s regal image: the story of the realities that, in many ways, it concealed.

Queen Victoria in Dublin, a print that appeared in The Illustrated London News, 21 April 1900

WD: I am really fond of the presidential chair – the former presidential chair, I should say – because I think it just says so much about the story of Dublin Castle post 1922. Just to explain: there were two thrones made at Dublin Castle during the reign of Queen Victoria, possibly for one of her royal visits. Each of them had a ‘VR’ for Victoria Regina on a little oval at the top and there was a little crown at the top of the back of the chairs. They were covered in red silk brocade with the royal coat of arms and shamrock diaper work all around. Following 1922, the Castle was used for a while as courts and then in the 1930s it started to be used again under Eamon de Valera as a place for State entertaining. When de Valera passed our new constitution in 1937, we elected our first president in 1938. And looking for a suitably impressive setting for the new Head of the Irish State, they chose St Patrick’s Hall. But they also took one of the old thrones and refurbished it: they cut the crown off the top, wiped out the ‘VR’ on the little oval and reupholstered it in blue with a gold harp on it. And that chair was used for every presidential inauguration from Douglas Hyde to Mary McAleese. For me, that chair represents everything about how the Irish were quite happy to assimilate in certain ways, after 1922, what had been left behind. They removed the royal symbolism, but then appropriated the item to create a suitably impressive image of the new Irish State. To me, it sums up a very curious aspect of Irish history which I think warrants a lot more examination.

William Derham and Myles Campbell with the former Irish presidential chair

DD: I noticed that in the title of the exhibition the ‘a’ in Making Majesty is turned on its head, and I was wondering if it was indicative of a sense of subversion in your exhibition.

MC: This is an interesting question. It is something the designer came up with by herself. When I saw it, it really appealed to me, because there is an element in the exhibition of telling a slightly subversive story or the other side of a story. If we take an example: we have someone like the Marquess of Buckingham. There is a great big portrait of him as viceroy in the exhibition, and we have a little cartoon in the case next to that portrait, and I think the two objects very much tell the story of him making this idea of a majestic image and then that image being challenged in print media. Basically, Buckingham created a very impressive Throne Room here, he remodelled St Patrick’s Hall, its great ceiling was paid for by him and is still there today – in short, he had a very clear sense of purpose in doing that to enhance his own image and the image of the court. But while he was doing this work in the 1780s he moved out of Dublin Castle and his baby was born in the Royal Hospital at Kilmainham, which was a soldiers’ hospital. The press at the time didn’t like him very much and thought this was very funny that the son of the king’s representative in Ireland would be born in what they called ‘a dirty old soldiers’ hospital’. So they sketched this little cartoon showing the level to which they felt the king’s representative in Ireland had sunk by having his baby delivered by a soldier with a wooden leg. There is a bawdy speech bubble coming out of his mouth, which I won’t repeat here, but which you can see in the exhibition. For me, that’s what I mean about this subversive story – it’s the story of the making of the image and then the challenging of that image by print media, by the public, by those who didn’t agree with what it represented. And when the ‘a’ turned on its head came up in the design I thought that actually really symbolises for me the story that we’re telling. But it’s important to say that this isn’t us trying to revise history. It is actually us trying to excavate forgotten stories in that history and tell an honest story of who these people were, what sort of image they wanted to create and how successful or not they were in creating that image. It is looking beneath the surface and looking at the other side of the story to some degree.

DD: What would you hope visitors will take away from the exhibition?

WD: I like visitors to come in and look through the exhibition and go: ‘Wow, I never knew that, that’s interesting.’ I’d like people to develop a want to look a little bit deeper everywhere they go and to realise that any story is just a little bit more complicated, but all the more interesting for that complication.

MC: I’d like them to take away from this the fact that the story of Ireland and the story of Dublin Castle is a complex one, it is not an easy one. I think by doing this kind of exhibition we have tried to engage with that complexity. We’ve tried to scratch below the surface, we’ve tried to show some of the good and the bad of the image that was created here of the court, and I’d like them to understand that there was – as the records and archives show, and these objects explain – a lot more nuance to that story. And if that helps visitors see things in the round, then that would be really good from my point of view.

Making Majesty: Building and Borrowing the Regal Image in Dublin Castle runs until the 28th of April 2018 in the State Apartments Galleries and is open every day from 9.45 am to 5.45 pm (last admission at 5.15 pm).

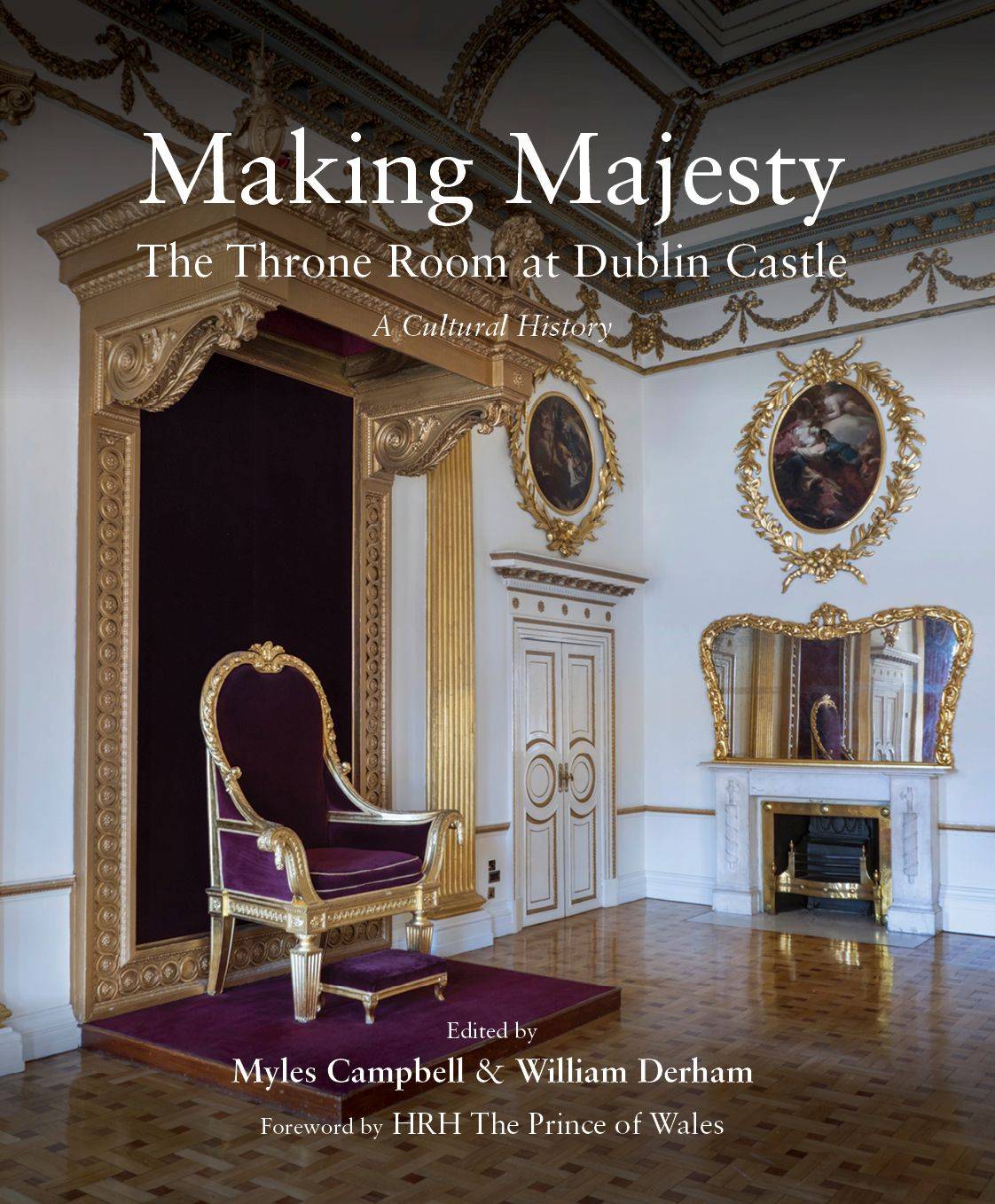

A collection of essays, edited by Myles and William, accompanies the exhibition: Making Majesty: The Throne Room at Dublin Castle, A Cultural History (Irish Academic Press, 2017).