By Dr Myles Campbell, Collections, Research & Interpretation

On 9 November 1849, Queen Victoria awoke to a surprise. Waiting to be unwrapped were two gifts from her husband, Prince Albert, which he had purchased during their visit to Dublin three months earlier. Recording the moment in her journal, Victoria remarked upon the novelty of this Irish surprise:

My beloved one gave me 2 such beautiful souvenirs, both made after those very curious old Irish ornaments we saw in the College, in Dublin … So dear & kind of him to have thought of this, & so valuable, for no one has anything like them.

One of these two special gifts was a replica of a tenth-century Irish brooch that had been found at Ballyspellan, Co. Kilkenny in the early 1800s. The replica was made by Edmond Johnson and was purchased by Prince Albert from West & Son Jewellers of Dublin’s College Green. As well as providing his wife with a unique memento of their Irish visit, Albert had another ‘deliberate’ purpose in shopping at West’s. Sensing a responsibility to encourage Irish artisans against the devastating backdrop of the Great Famine, he set an early example of royal support for Irish jewellers, in the hope of boosting their sales. This ‘top down’ approach appears to have had some success. By the 1850s, several Dublin jewellers were producing the Ballyspellan ‘Victoria’ brooch. Such was its popularity that it was displayed in one of the most prominent shop windows of all – the Great Industrial Exhibition on Dublin’s Leinster Lawn, in 1853.

The copy of the Ballyspellan brooch made by Edmond Johnson of Dublin and purchased by Prince Albert for Queen Victoria in 1849. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

In 1821, West & Son had provided a magnificent shamrock-shaped box as a gift for King George IV on his visit to Ireland. Made of Irish bog oak and decorated with diamonds and pearls, it mixed Irish motifs with royal insignia. Like the ‘Victoria’ brooch, it featured an Irish inscription: ‘Go mbeannughudh Dia thu’, meaning ‘May God bless you’. This Irish greeting was later reciprocated by the King, whose last public words on departing Ireland were: ‘God bless you all my friends, God bless you all’. In both its form and materials, the box, like the ‘Victoria’ brooch, was a physical manifestation of the idea that the crown and the Irish language could go hand in hand – that Irish nationalism and loyalism were not mutually exclusive – that different versions of Irishness could exist side by side.

The box made by West & Son of Dublin for the visit of King George IV to Ireland in 1821. © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018.

Twenty-eight years later, in 1849, a reversal of influences in royal patronage meant that West & Son were no longer proffering their wares in the hope of attracting royal interest, but were now being sought out in person by members of the royal family. Although only a small gesture, Prince Albert’s purchase was, nonetheless, a useful attempt to set a standard for the Irish Ascendancy, encouraging them to look to Dublin rather than abroad for their material needs.

At Dublin Castle, the Viceregal Court was doing likewise. Among one of the earliest owners of a version of the ‘Victoria’ brooch was the Countess of Clarendon, wife of the then Irish Viceroy. Looking through the account books and records of the Castle, it is also apparent that Irish jewellers were becoming increasingly involved in modifying and maintaining objects in its collection. The most important of these were the so-called Irish Crown Jewels, which would later be stolen from Dublin Castle in a famous robbery in 1907. Once the prerogative of the Royal Wardrobe in London, these commissions were one way in which the Viceregal Court attempted to remain on the right side of the debate surrounding Irish nationalism and elite consumption in the nineteenth century.

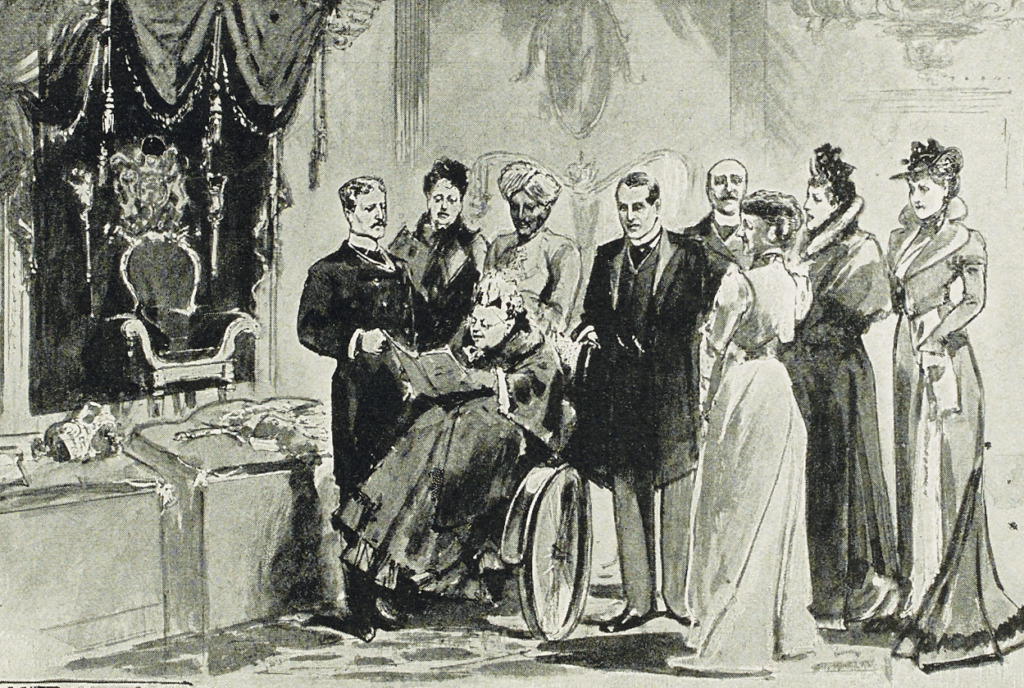

One of the most important objects that fell under the care of the Irish jewellers to the Crown at Dublin Castle was the Irish Sword of State. Made in London in 1660–61, this spectacular artefact represented the authority of the British monarch in Ireland, and once rested across the throne in the Castle’s Throne Room. According to the Castle’s account books, the Sword and its associated maces were well cared for by Ireland’s jewellers. In 1819, a clean by Waugh and Sons of Dublin cost the princely sum of £3.19.7. An image of Queen Victoria surveying the State regalia in the Castle’s Throne Room, in April 1900, suggests that the work of these jewellers was still garnering the royal seal of approval at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Queen Victoria inspecting the regalia in the Throne Room at Dublin Castle, attended by a group including the Viceroy, Earl Cadogan and her servant Abdul Karim, April 1900.

Over time, sustained royal and viceregal support for the Irish jewellery trade was echoed by Irish peers and their families. Among the objects commissioned by such families was a small coronet made for the Countess of Granard in about 1890. Complete with hair pins to hold it in place, it was made by Dublin goldsmith Edmond Johnson. Johnson’s were no strangers to patronage of this kind, having been the very makers of the brooch purchased by Prince Albert for Queen Victoria in 1849.

Coronet made for the Countess of Granard by Edmond Johnson, c. 1890. Dublin Castle Collection.

In a remarkable twist of fate, Edmond Johnson went on to make the Liam MacCarthy Cup for Ireland’s All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship in 1922. Once the maker of jewellery for the Crown in Ireland, Johnson had now become the maker of one of the most prominent cultural artefacts of post-independence Ireland.

On the surface, this story would appear to be one of complete transformation, where patterns of patronage changed forever following Irish independence, in 1922. But on a deeper level, the appointment of Johnson as maker of the MacCarthy cup says more about continuity than about change in Ireland. Much like the ‘Victoria’ brooch and the shamrock-shaped box made for King George IV, it speaks of a world where different versions of Irishness could still exist side by side, whatever the political circumstances.

The original Liam MacCarthy Cup made by Edmond Johnson in 1922. It was presented annually to the winners of the All-Ireland Senior Hurling Championship until its replacement in 1992. Courtesy of the GAA Museum, Croke Park.

Today, the shamrock-shaped box made for King George IV and the Irish Sword of State are back on display in Ireland. On loan from the Royal Collection until April 2018, they can be seen, along with the Countess of Granard’s coronet, as part of our Making Majesty exhibition at Dublin Castle. The original Liam MacCarthy Cup is on permanent display at the GAA Museum, Croke Park. The Irish Crown Jewels, however, remain unaccounted for. But that is a story for another blog post …