By Laura Fitzachary, Tour Guide and Co-Curator/Information and Education Officer

‘It must, however, be remembered, when considering their good fortune, that in the day in which they lived beauty was all powerful.’

– Frances Gerard on the Gunning sisters on their arrival in Dublin, 1750

Dublin Castle was the centre of court culture and home of the Season in eighteenth-century Ireland, providing a social platform on which members of, and visitors to, the viceregal court could flaunt their ability to follow and execute changing trends from London and Paris. The idea of this exhibition arose from our interest in social history and the age-old human inclination to do oneself up for an occasion. Though some, of course, did not care what they looked like, those who did take advantage of the stage the viceregal court offered were able to channel its interest in fashion and its ability to afford and fuel the latest trends. Such trends trickled down the social ladder and they also provided an opportunity to climb it. However, although the advantages of being fashion-forward determined social status, the exhibition shows that the personal cost could be high.

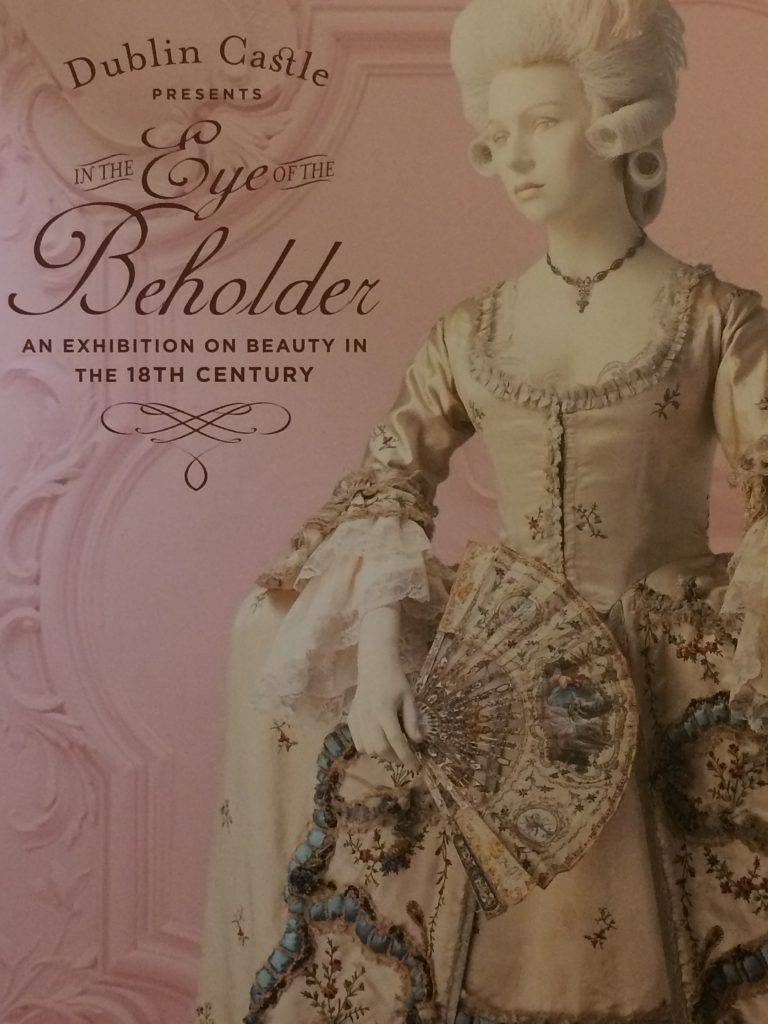

My colleague Bronagh Dempsey and I looked at using beauty as a theme in and of itself, taking as our point of departure the Greek proverb that ‘beauty is in the eye of the beholder’ and the fact that while the appreciation of beauty transcends centuries, it also constantly changes. To make the actions of women and men at the viceregal court in Dublin Castle more relatable, we broke the exhibition up into five topics: men’s fashion, ladies’ fashion, make-up, hair and hygiene. In combination, these topics create a typified example of a lady or gentleman attending the Irish court in the eighteenth century, but taken on their own, each category reveals that there were constant shifts in trend. Visitors of the exhibition will also learn about the harsh reality behind maintaining the beauty standards of the eighteenth century.

For example, the need to conform to the ideal whiteness at the time forced some to use drastic measures and products. A paler pallor meant one did not need to go outside and therefore was an indication of wealth. This attraction to white applied to hair, skin and even teeth – by any means necessary, including the experimental use of acids. Lipstick concoctions at the time could also prove toxic, and clothing was redeveloped to create shape-enhancing corsets and knee-length coats to expose the lower legs. Despite a growing awareness of the detrimental side effects of some treatments and fashions, eighteenth-century Dublin strove hard to keep up with fashions set in London and Paris.

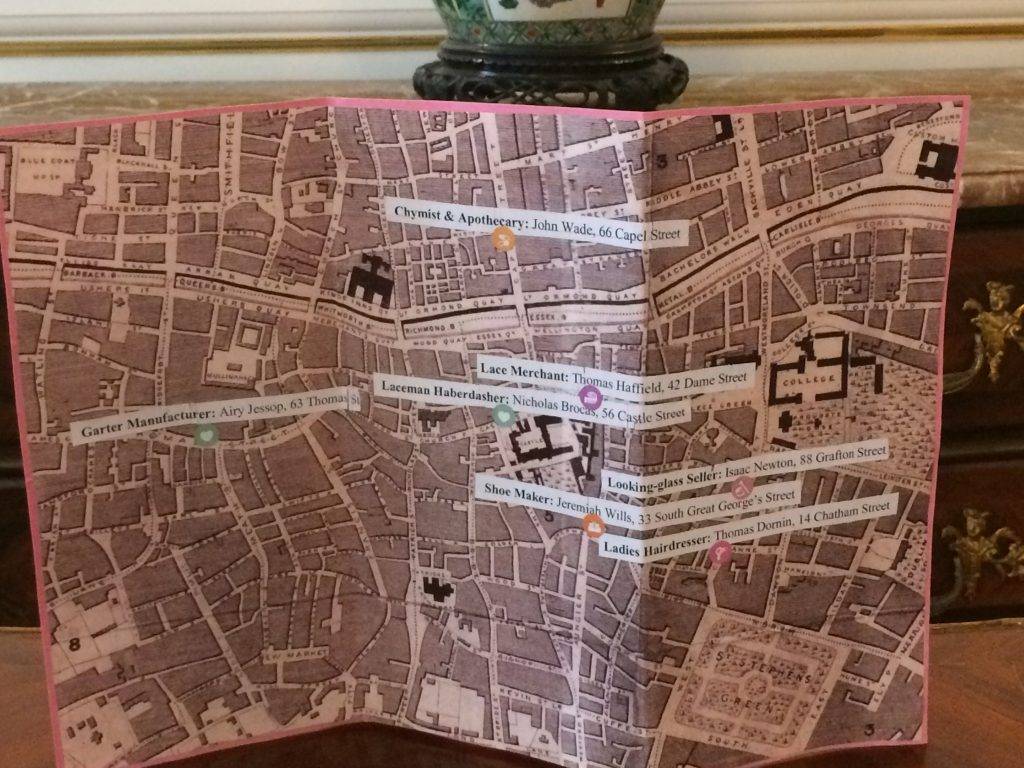

A map with Dublin Castle at the centre shows visitors the close proximity of local milliners, haberdashers, silk weavers, embroiders and looking glass sellers, all conveniently located in the nearest streets to provide visitors to the court with everything they needed. Two mannequins wearing eighteenth-century attire and wigs by Val Sherlock illustrate the accoutrements of fashionable ladies and gents of the time. Rather than using white wigs, we chose two brunettes with the lady’s wig altered to achieve the same hue as the ‘do’ of a Georgian lady at court.

In the Eye of the Beholder: An Exhibition on Beauty in the Eighteenth Century runs until 20 September in the Apollo Room in the State Apartments. The exhibition will give visitors insight into a more personal side to courtly figures, peel back the idea of beauty and reveal by what means it was actually achieved. We hope that you will enjoy it and leave it to you to decide the all-important question: if beauty is in the eye of the beholder, was it worth it?